There aint no party like a third party

Current polling makes dire reading for the Conservatives, but Labour's own precarious position leaves the door open for a new challenger.

Well hello there!

Thank you very much for subscribing to Plain Speaking English - I hope you enjoy this first instalment.

Of course, while all the lovely data come(s) from YouGov and they do pay my wages, these views and ideas are entirely my own.

Feedback, debate, and thoughts are of course all very welcome - you know how to reach me!

All the best, and I hope you are having a lovely holiday season,

Patrick

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the focus of the first ever Plain Speaking English newsletter will be parties.

But no - not those ones! Well, they might get a mention…

Instead, I’d like to highlight some trends and figures in current YouGov polling which lead me to believe that the current British political environment is ripe and ready for a fresh ‘third party’ injection.

“But you will never break the two-party system”, I hear you cry!

And perhaps that’s right, but humour me a while…

Vote intention slides

Firstly, let’s start with the headline figures. It is news to precisely no one that the Conservatives have been struggling in the polls of late. Downing Street Christmas parties, Johnson’s handling of and involvement in various (alleged) scandals and misgivings, and concerns over the spread of Omicron have fed into more medium-term problems for the government such as rising prices, tax burdens, and bills.

While we might characterise the succession of tales and photos of parties and gatherings last year, at a time when the rest of the country were in lockdown, as the straw that broke the camel’s back (in that only after they emerged did Labour establish a solid polling lead), the Conservatives have been on a downward slide in vote intention polling since the middle of the summer.

At the same time, we are seeing increasingly poor approval ratings for the government and for Boris Johnson himself, reaching levels we haven’t recorded since Theresa May’s struggles to pass a Brexit deal through parliament.

It is worth keeping in mind that none of this is particularly abnormal for mid-term governments. Incumbents pay a price for being incumbents - they have to make decisions and to govern, and inevitably those decisions and that governing will upset some people and cause voters to turn against them.

The question - or the problem - is always if and how they can bounce back ahead of the next General Election.

Switching away

Beneath the surface of vote intention headlines there are more worrying trends for the Conservatives which bring into question how well, if at all, they will indeed recover. Or perhaps highlight the scale of the recovery work they now need to do.

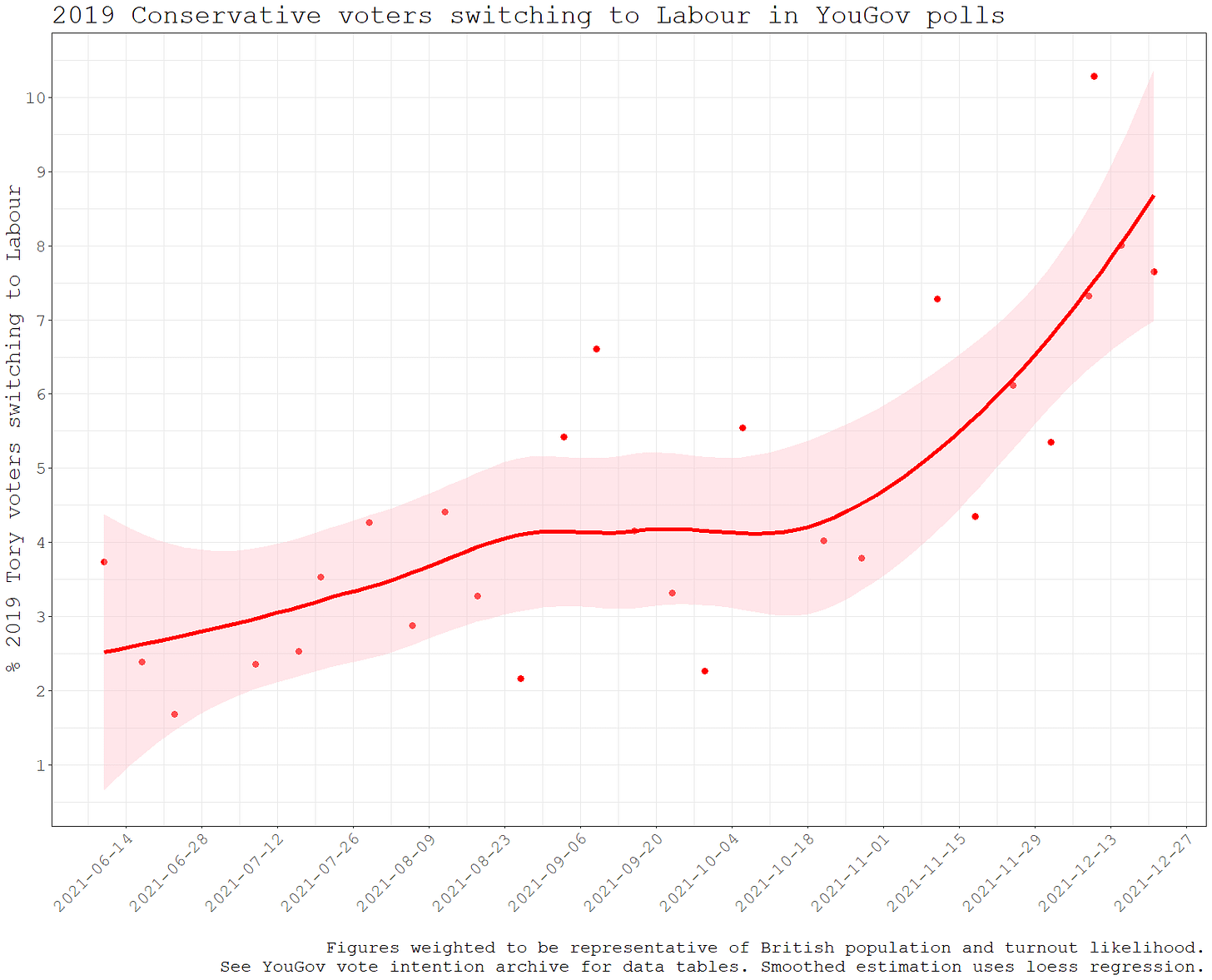

For starters, direct switchers from the Conservatives to Labour is creeping up toward 10%. That is to say, somewhere around one-in-ten 2019 Conservative voters now intend to vote Labour.

This was not previously the case earlier in the year, as the graph below shows; only since late November has that figure been consistently above 5%.

What do those recent figures look like in context? Well, YouGov’s final pre-2019 General Election polls estimated that the Conservatives were winning around 6-8% of 2017 Labour voters en route to their biggest electoral victory since the 1980s.

What may trouble Johnson and the Conservatives even more is that the rate of switching to Labour appears to be greater - and accelerating faster - in the North of England than in Wales, the Midlands and the South.

This is further indication that those ‘borrowed votes’ which handed the Conservatives victory in so many ‘Red Wall’ seats in 2019 are drifting away.

What’s more, Labour leader Keir Starmer now has a double digit lead in YouGov’s ‘Best Prime Minister’ tracker (latest figures: Starmer 34%, Johnson 22%).

So, not only do Labour enjoy a healthy lead in vote intention polls, and are winning significant numbers of voters directly from the Conservatives, but the public also appear to now believe that their leader would make a better PM than Johnson. As we well know, winning that leadership contest is a huge part of any General Election horserace.

A finely balanced lead

But the truth is that Labour’s now-strengthened position is actually pretty precarious. The party still trail the Conservatives on who would best handle the economy, and on the fastest growing ‘most important issue’ in current polling - immigration and asylum. Voters clearly still do not trust Labour on key policy areas.

Further, there is evidence of high levels of apathy and volatility among both parties’ voter bases. For instance, the proportion of Conservative voters who either do not know who they would vote for or would stay at home is around three times higher than the proportion currently indicating that they would switch to Labour.

This leaves a huge constituency of former Conservative voters up for grabs - voters who are clearly not enamoured enough with Starmer or Labour to switch in their direction, and could quite easily go back into Johnson’s voter coalition. Or elsewhere.

Equally, though Labour’s polling lead looks quite solid for now, still around 20% of their 2019 voters are not currently backing the party, and instead intend to vote for someone else. As recently as October, this was as high as one-in-four 2019 Labour voters.

Now of course, these are only vote intention figures taken from polls with no General Election in sight (and - health warning, they are all cross-breaks from nationally representative polls!). But taken together, I’d argue that the current levels of volatility, dissatisfaction, and distrust so abundant in the British political scene make it ripe for another ‘third party’ intervention.

(Third) Party rockers in the house (of Commons) tonight

True, the last time an emerging party were able to turn the British political system on its head and win elections was the Labour Party in the 1920s.

But we should not underestimate the ability of new - or existing challenger parties - to disrupt and effect change in British politics at or from the margins.

We need only think of the Liberal Democrats forming a coalition government with the Conservatives in 2010, Scottish National Party (SNP) electoral success forcing David Cameron to hold a referendum on Scottish independence in 2014, and the continued Eurosceptic pressure applied by Nigel Farage and UKIP (again largely on the Conservatives) which ultimately resulted in the staging of the 2016 EU Referendum - and of course the UK’s subsequent withdrawal from the bloc.

What tends to define the success or failure of third parties in British politics is whether they are able to successfully capture causes or public moods and put together a voter coalition around them.

In the above examples, Labour were organising around a freshly enfranchised working-class electorate in need of parliamentary representation, the SNP leading the growing political movement for Scottish Independence, the Liberal Democrats capturing intense, firebrand moments such as public resistance to the Iraq War and tuition fees, and UKIP riding a wave of Euroscepticism, public negativity toward immigration, and a sense among many voters in the North and Midlands that they had been ‘left behind’.

Thinking of a more recent instance, the failure of the Change UK project can arguably be put down to there simply being very little voter demand for what they were offering - or at least that they occupied very similar territory to the already-established Liberal Democrats and a Labour party who would eventually pivot toward offering a second referendum on EU membership.

Apathy and frustration toward the two largest parties alone is not enough for the magnitude of third-party intervention seen in the examples above. But could growing concerns with the country’s immigration system and migrant channel crossings fuel another ‘revolt on the right’? Could the Green Party capture rising worries about the environment and climate change to transform their electoral success at a national level? Could someone forge an electoral coalition around issues which may not currently be high on political radars but with which the public are deeply dissatisfied, such as housing, welfare and benefits, or transport? The opportunity, I think, is certainly there.