Local elections 2024: Liz Truss effect?

Data from local elections suggests Conservatives are still very visibly paying the price for the former PM's economic experiment

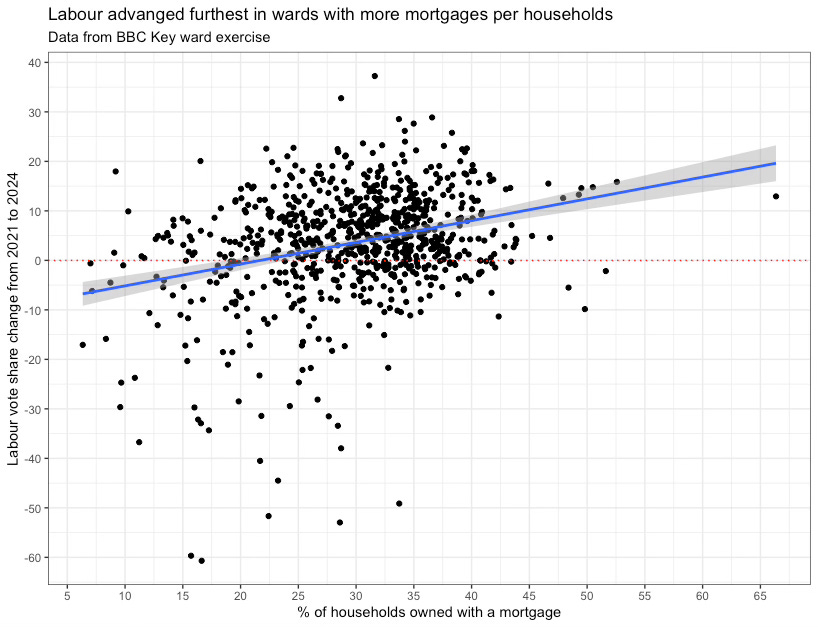

With all but one local council now declared out of the 107 who held elections on Thursday 2nd May 2024, I wanted to bring out one finding which really struck me as the count came in over the last couple of days - the evidence of a ‘mortgage premium’ on the Conservative Party losses.

The headline results from the local authority, mayoral, and police and crime commissioner across England and (in the case of the latter) Wales are quite unambiguous: the Conservatives have taken a beating.

While the Rishi Sunak’s party won’t quite lose over 500 councillors, as some were briefing before the count began, they have nonetheless lost around half of the total number of seats they were defending.

Meanwhile, the Conservatives have also lost around 40% of the police and crime commissioner positions they held going into the election. That figure would have no doubt been higher if the electoral system had remained in two rounds; the Conservatives won many ‘first past the post’ contests over Labour or the Liberal Democrats by a slim margin, with the other of the latter two in third with a significant share.

In terms of the mayoral races, while there was a statement win (against a big swing) for Conservative-incumbent Ben Houchen in Tees Valley, rumours that Susan Hall would outperform expectations and deny Sadiq Khan a third term as London Mayor were wildly out. In reality, Khan won by a comfortable 11 point margin.

And in one of the real headline moments of the count, Labour’s Richard Parker managed to squeeze out the Conservative in Andy Street in the West Midlands Mayoral race by a mere 1,508 votes.

There is no correct read from these results other than that they spell deep, deep trouble for the Conservatives. They lost seats in all races across all areas to all parties on all fronts: Labour, the Liberal Democrats, and the Greens.

While Reform didn’t make many waves in terms of winning seats (just the two), they did contribute to Conservative struggles, particularly in the North, by eating heavily into their vote share in the minimal number of places they actually stood. They also had a strong showing in the Blackpool South parliamentary by-election (won, in thumping fashion, by Labour), almost pipping the Conservatives to second place.

The Liberal Democrats managed to symbolic accolade of beating the Conservatives in terms of councillors won on the night, finishing second on that metric behind Labour.

Meanwhile, the Greens had a fantastic night, winning over 180 council seats with a net gain of over 70. Their performances may become one of the stories of coming local election cycles if Labour do win a parliamentary majority and the Greens successfully crystallise their position (among many others, such is the diversity of their voter coalition since 2019) as a home for protest voters on the left of the political spectrum.

Many headline analyses and commentary of the results have already been conducted, including this writeup by Sir John Curtice, Stephen Fisher, Rob Ford, and myself (which includes an explanation of the ‘projected national share’). What I would like to focus on in this post is a specific but very strong correlation in the results which speaks to a wider development in vote intention and vote behaviour in British politics since the last election.

Namely, the relationship between Conservative Party vote performance and the percentage of households with mortgages at the ward level. I should say that this story is just one among many different dynamics which were at play on Thursday’s votes, but is one which particularly interested me.

Each year, the BBC Election Results team (on which I work as a psephologist) collects and looks at ward-level results and background data from a number of key councils as part of its ‘key ward’ exercise.

The data from this year’s 811 key wards suggested that in wards with less than 22% of households owned by a mortgage, the Conservative vote share change on 2021 was -8 points. In wards with over 36% of households owned with a mortgage, the vote Conservative share dropped by 13.5%.

Conversely, Labour’s vote was up by 6.5 points in wards with the highest proportion of mortgage holders, and actually down by 4.1 points in those with the fewest.

This is no statistical anomaly nor coincidence. In fact, we can draw a clear line between the key ward results and evidence from YouGov survey data, written up by my colleague Chiara Ricchi, regarding vote Westminster vote intentions among people with different housing situations.

Chiara found that while outright homeowners are currently breaking for the Conservatives over Labour by a margin of 26% to 22%, Brits with a mortgage are going strongly toward Labour, by 35% to 15%.

Why would Westminster vote intention be so divisible by home ownership status? Why do we see such clear patterns in the ward level results?

The simple explanation: this is a tangible public opinion reaction to the stark rise in mortgage interest rates in 2023 associated with the economic fallout from the mini-budget introduced by Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwaerteng during their brief stint in power in October 2022.

Despite being 18 months ago, mortgage rates have remained high (compared to the pre-Truss baseline) ever since the Autumn 2022 mini-budget caused shockwaves throughout British financial markets. So, not only did that fiscal event affect people looking for their first (or new) mortgages during 2023, it has continued to affect those looking for their first mortgage now, and has impacted everyone remortgaging or renegotiating their mortgage over the same period.

Figures estimate that around 285,000 mortgages were up for renewal this quarter alone. This means that across Britain, every month, tens of thousands of voters are very quickly reminded of those moments in Autumn 2022 when the then Conservative government oversaw a self-inflicted economic shock, and the party were forced to remove their newly-anointed leader within just six weeks of her being selected by the membership.

And so rather than those moments of madness fading into memory, even in the context of now falling inflation and wages growing, somewhere around 1 million households a year find themselves suddenly paying thousands of pounds extra for it.

An under-developed piece of thinking in terms of plans for a general election date is that while ‘going long’ and waiting until the autumn or winter may well maximise the chances of any economic recovery being felt in the payslips and back pockets of British voters, it also drags more and more of them into the pool of homeowners paying a direct price for the economic policy choices of a Conservative government.