Germany. Nothing but Germany.

I've spent the last three months of my life obsessing over voter data in Germany, so you don't have to.

This week, we at YouGov released our final MRP projection and regular vote intention monitor for Sunday’s snap German federal election. MPs will be elected by Germans to the Bundestag (parliament) tomorrow, with exit polls expected in the early evening, and results following shortly after.

Unlike counts in some other countries we could mention, the whole thing will be wrapped up within a matter of hours, rather than days.

While the polling industry disagrees somewhat regarding specific shares for specific parties, and eventual makeup of the Bundestag in terms of parties getting representation, the agreed-upon expectation is that we are headed for a change in government after just three-and-a-half years of an Olaf Scholz premiership.

His is a premiership by the why which has cratered in terms of approval ratings; 77% of Germans told us they disapproved of their government’s record to date in our latest YouGov data, versus 15% who said they approved. Much as there was with the Conservatives and Rishi Sunak in the 2024 British general election, a strong feeling of “get them out” dominates.

The CDU/CSU Union, formerly led by Angela Merkel and now by former corporate lawyer and MEP Friedrich Merz, are expected comfortably be the largest party. The current SPD-led government looks set to be yet another casualty in the recent global trend against incumbents.

How did we get here, and what has the election been about?

I’ve been working extensively on YouGov’s polling for the election, mainly the MRP, for a few months now, having also done so for the last federal election in 2021 (we didn’t have an MRP then, though).

This year’s contest feels mightily different from the previous in a number of ways - not least because of the early, ‘snap’ nature of the vote which was thrust upon Germans after the collapse of the ‘traffic light’ coalition in November.

As it went, I happened to be in the Reichstag (the German parliamentary buildings) the day the government fell. I had nothing to do with it, promise!

That day (6th November), Chancellor Olaf Scholz (SPD) met with Finance Minister Christian Lindner (FDP) to attempt to salvage a programme for continued government from the bombsite of disagreements and in-fights over fiscal policy.

They failed. And here we are, facing only Germany’s fourth early election in its history.

The 2021 election was contested as Germany, and Europe, were in the twilight of the Covid-19 pandemic. The key issue was essentially that - how would Germany recover, financially and socially, from the biggest global shock since the financial crisis.

This time, while it is not the topic that the SPD (nor either of their coalition partners) would have chosen, it has very much been an immigration election - at least in terms of public priorities. That has, of course, played into the hands of Germany’s political right.

Our polling from earlier this month reported that no fewer than 35% of Germans saw immigration as the top issue facing the country today, while 56% placed it in their top three.

By contrast, those figures for ‘the economy’ were 16% and 35% respectively.

That same polling found that 80% of Germans believe immigration has been too high in the last decade, and that half believe immigration has been generally bad for the country.

Perhaps it is no surprise then that the biggest political moment of the campaign came when Merz and the Union controversially cooperated with the AfD to secure the votes to pass a (non-binding) immigration-cutting motion in the Bundestag. A momentary unification of the parliamentary right wing to place a marker in the sand on the topic most pressing to the German public.

What are YouGov’s projections?

The German 2025 federal election is yet another contest in which, if the polling is right, incumbent parties will get a hiding. Particularly so the SPD as the leading governing party and Olaf Scholz as Chancellor, but also the FDP - who we project will drop out of the parliament altogether. The Greens, the third coalition partner, will likely emerge relatively unscathed, though.

Germany’s electoral system gives every voter two votes – one for a ‘direct mandates’ representing their local constituency, and a second ‘regional list’ vote from which overall parliamentary seat allocations are calculated.

German electoral law stipulates that to qualify for representation in the Bundestag, parties must either win 5% of the national vote (all regional list votes, tallied) or win three ‘direct mandates’ in the form of constituencies. Hence, for instance, BSW and the FDP can win 4.6% and 4.5% of the vote respectively but be allocated no seats (as above).

As well as the anticipated change in government, the other major story of the election is, as with so many countries across Europe, the rise of the far-right.

The AfD look set to effectively double their vote share from the 10% they managed in 2021, and become the second largest party in the Bundestag.

To fuel their polling rise, the AfD have been winning support from the those who previously voted SPD, the FDP, smaller (non-Bundestag) parties, and even the Union, who themselves have almost exclusively been winning their extra votes from former SPD and FDP backers.

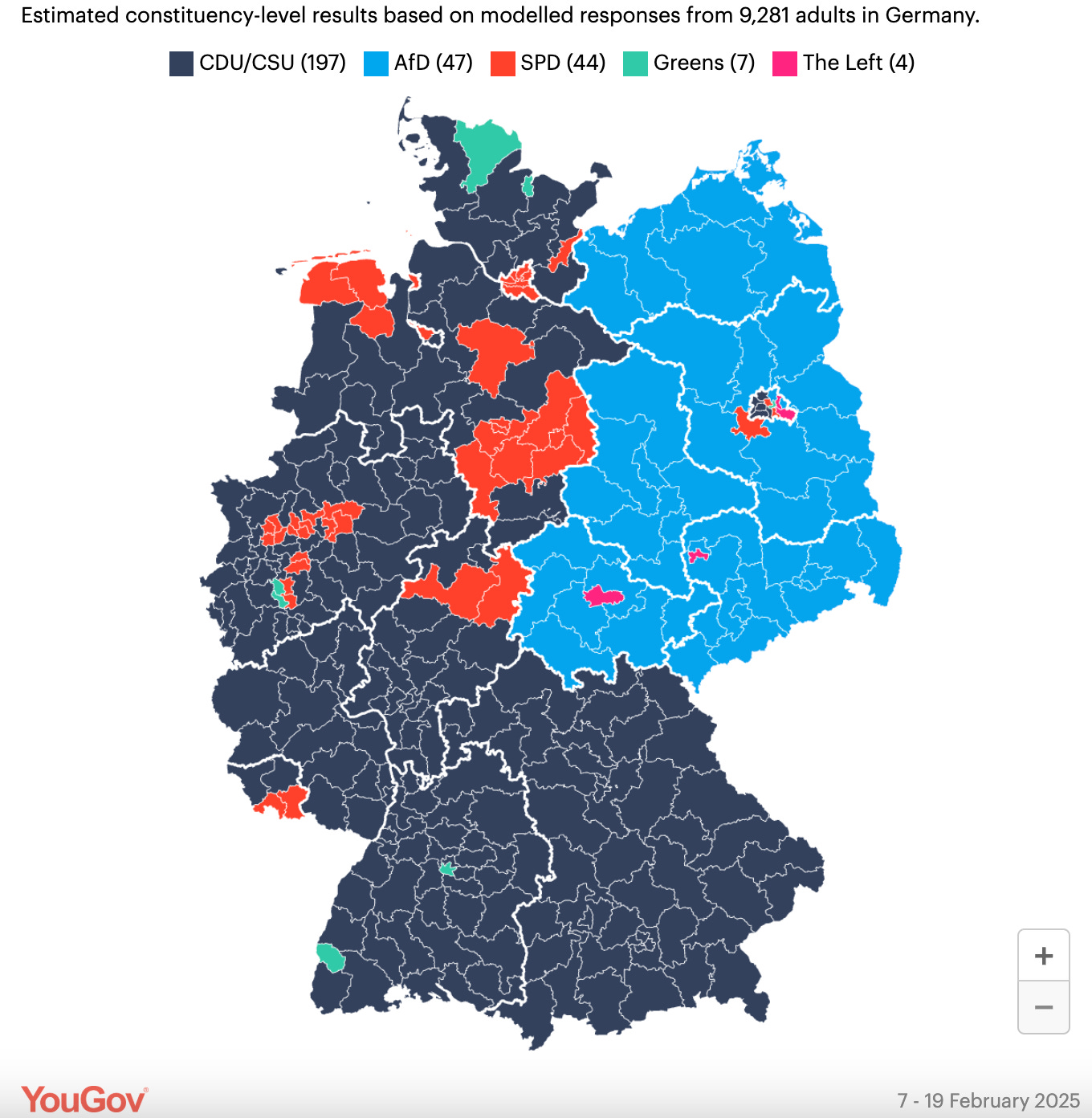

Looking at map of projected constituency wins, Germany’s old wounds are figuratively lit up in bright lights. The contrast between the old German East (the five Bundeslands of Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Saschen, Sachen-Anhalt, Thüringen, and the east of Berlin) and West (the remainder of Germany, including West Berlin) is stark.

The AfD are projected to win all but five constituencies in the former East Germany, and precisely zero in former West Germany.

The old Iron Curtain is now a barrier against a blue tide.

What possible governments are we looking at, and will the far-right be involved?

Despite their rise in popularity and prospective occupation of something in the order of 20%-25% of parliamentary seats available, all other German political parties have promised to maintain ‘the lockout’ of the far-right from government.

In this sense, Germany stands apart from other European nations, such as Sweden and the Netherlands, who have brought far-right parties into governing coalitions.

Depending on the eventual outcome of the vote and the exact composition of the parliament, government formation could be tricky - especially if the AfD are indeed occupying so many seats yet no party wanting to work with them.

The reason being is that there are three parties close to that 5% threshold (Die Linke, BSW, and FDP). If they were to each make it into the Bundestag, this will significantly reduce the number of seats which the other four (larger) parties will win.

As I explored and outlined for my piece on the YouGov website yesterday, in a five-party Bundestag - the central projection of our MRP model - Merz and the Union could partner directly with the SPD and together enjoy a seat total well above the 316 required for a parliamentary majority.

This would be a relatively simple task, one which the two parties have often done before, and would create a stable governing majority.

A ‘Black-Green’ coalition between the Union and Greens could even be possible, if both parties perform well in the final vote share.

A seven-party parliament (or rather eight, if we include the protected minority South Schleswig Voters' Association party) makes coalition-building maths very difficult versus a five or even six-party parliament.

A fractured Bundestag in which Merz would be forced to work with not just one but two other parties to form a government would come with two sizeable risks:

The new coalition could fall to the same fate as the outgoing current government - collapse, forcing new snap elections. Negotiating between and managing the interests of three parties with three distinct voter bases is no mean feat, as Olaf Scholz and the SPD found out. We don’t know how kindly, if at all, German voters would react to being sent to the polls early again.

If the Union partner with both the SPD and the Greens to form the government, that leaves the AfD as essentially in a very clear position as the key opposition voice. Though of course the other, smaller opposition parties will be competing for airtime in such a parliament, if the far-right alone become the lightning rod for all anti-government sentiment that is a potentially highly dangerous situation for German politics and democracy (and for the electoral prospects of mainstream parties themselves).

What about Germany’s political left?

Another noteworthy story of this election has been the contrasting fortunes for Die Linke and BSW over what was otherwise a fairly stable and uneventful (in terms of the polls and public opinion, at least) election campaign.

These two main parties of the German left flank have essentially swapped places in the polls - and also their respective chances of making it to the Bundestag

The central projection in our first MRP on 17 January was that Die Linke would drop of the Bundestag altogether, failing to reach either the 5% national vote threshold or get the three constituency wins required to qualify for parliamentary representation

Now, Die Linke have gone from an estimated 2.9% of the national vote in mid-January to no less than 7.5% in our final projection. Their campaign has really sprung to life after a slow start, with younger voters in particularly quickly connecting with parliamentary leader Heidi Reichinnek. She has taken a much more central role in Die Linke’s campaign efforts (particularly on social media) in recent weeks.

We’ve seen the opposite trend however for Germany’s newest political party, the ‘Alliance for Sahra Wagenknecht’ (BSW) – a former Die Linke politician who split out from the party in 2023 to form her own parliamentary grouping.

The BSW campaign has been a highly personalised one, with Sahra Wagenknecht’s face featuring heavily on party literature and posters occupying the social media feeds, lampposts, and roundabouts (yes, really!) of Germany.

In so doing, Wagenknecht hoped to lean into her relative popularity and high name recognition among many, mostly left-leaning, voter groups.

But our MRP projections suggest she and her party may not have been successful in this aim and could be facing exclusion from the country’s parliament altogether.

In our first MRP, we projected BSW to be on 6% of the vote, qualifying them for around 45 seats in the Bundestag. Our mid-campaign update MRP on 6 February had them on 5.4%, and approximately 40 seats. In our final MRP, their projected vote share has dropped to 4.6%, meaning they drop out of the parliament altogether.

It remains to be seen what the BSW will do from here, if they fail to make the parliament. The case for a bespoke political party in their niche position in the German political system might be difficult to justify, particularly if Die Linke perform as well as expected The projected 8 or even 9% of the vote for Die Linke would be double what they achieved in 2021.

A final thought

Perhaps this is just a reflection of the relatively short time in which I have been working in political research and elections, but it feels that snap election contests are a tool exercised by incumbents much more frequently now than in decades gone by.

Governments in the United Kingdom, France, Spain, and Germany, as just some examples, have all called snap contests within the past 18 months. Each time, the motivation of the incumbents in these races has been, at least to some extent, to try and catch their opposition off guard and unprepared, to focus dissenting internal-party voices and swing momentum around, and to force their opponents into errors or missteps under the sudden pressure of a campaign.

Only one incumbent has really managed to successfully achieve this - Spain’s Pedro Sanchez.

Looking at the projections for the German election tomorrow, I feel we can safely conclude one thing - Olaf Scholz is not Pedro Sanchez.

Only Pedro Sanchez is Pedro Sanchez.