Constituency majority bubble wrap

How the scale and efficiency of the 2019 Conservative victory provides a significant buffer against Labour electoral momentum

This is a pre-editorial version of my recent article for Conservative Home

With the polls now settling on something around a 30-point lead for Labour over the Conservatives, and quiet rumours abound of a possible early General Election, many are wondering just how bad an election result the Conservatives would be facing if an election were indeed to be held tomorrow.

The reality is that a 30-point lead is unlikely to sustain through until polling day itself – not least because a significant portion of said lead is not driven by direct transfers of (intended) votes between the Conservatives and Labour, but 2019 Conservative voters telling pollsters they “don’t know” who they would vote for at present.

Nonetheless, in a hypothetical world where Labour did win the election by some 50 points to the Conservatives’ 20, a wipe-out would be all but assured. On a uniform national swing (UNS) projection, the governing party could well be reduced to under 100 seats.

But while the Conservatives may be extremely unpopular as it stands, a 30-point defeat would be absolutely extraordinary. Furthermore, the maths involved for Labour to even win a majority is much trickier than many would automatically assume. Swings of the traditional, usual manner between contemporary British elections – somewhere between 3 to 5% - would not even get Labour close to victory.

Indeed, the scale of Labour’s task to even win a majority at the next election cannot be overstated. They need to add no fewer than 124 seats to their 2019 total to win an absolute majority. And such are the sizes of the majorities that the Conservatives have built up in many formerly-marginal constituencies up and down the country, Labour flipping almost 20% of the available seats in the Commons is no small task.

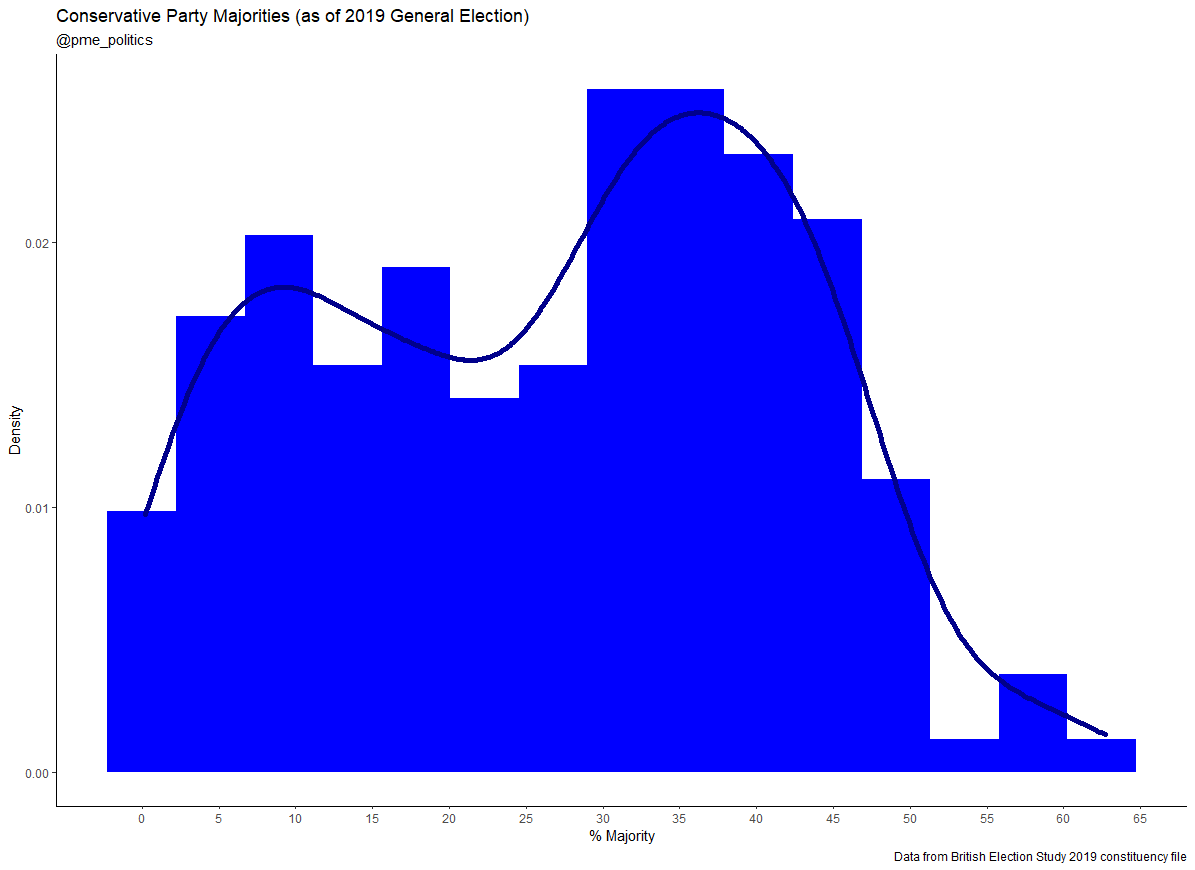

The plot below demonstrates the two movements Labour must make to get past that figure. First, a range of ‘low hanging’ fruit of Conservative majorities lie between 0 and 10 points. A swing to Labour of just 5% would be enough to take this raft of marginals. But a second, much larger peak, of Conservative majorities sits up at around the 30% mark. Far from being entirely made up of what we would consider traditional Conservative safe seats, the group between that first and second peak contains many traditional marginal and bellwether seats including Corby, Stevenage, Milton Keynes South, and Morecambe and Lunesdale.

If were to line up all Conservative constituencies (as of the conclusion of the 2019 General Election) in order of marginality, and assume that Labour lose no seats they won in 2019 (which is not at all guaranteed, with each of the Greens, SNP, Plaid, and even the Liberal Democrats breathing down hard on Starmer’s party in seats across the country), and each of the SNP, Plaid, and the Greens hold on to their respective seats, the constituency of Rugby sits on the majority line.

With a majority of 13,447, Labour require a 13.25 point swing to take the seat Mark Pawsey has held for the Conservatives since its re-conception in 2010. In any ordinary election, removing a four-term incumbent on a double-digit swing would seem fanciful to say the least.

That said, many Red Wall constituencies fell just three years ago in just this manner. While some, such as Don Valley and Warrington South, were captured by the Conservatives on the back of a ‘final push’ from momentum built up over multiple election cycles, others such as Great Grimsby and Redcar were taken rather strikingly on the night in 2019 on 15-point swings.

Looking further back down that line of Conservative constituencies, a swing of around 9 points would be enough to take every seat up to York Outer, and all but establish Labour as the largest party in parliament. A swing of that order seems much more achievable than 13.25, but still looks very large in historical context; in his thumping victory just three years ago, Boris Johnson achieved a swing against Labour of around 4.5 points, while Cameron achieved 5 in 2010. Even the swing that swept Thatcher into power in 1979 was just 5.2 points. Tony Blair’s 1997 landslide win was built on the back of a 10-point national swing.

That is where the cataclysmic 2019 defeat has left Labour – requiring peak Blair-level momentum to simply get back into power via coalition or minority government.

Other scenarios seem more improbable still. To win an effective majority able to sustain small rebellions would require Labour to produce a swing of around 15 points. To reach a Johnson-level majority, Labour would need a 17.5 swing. To win a landslide, they would need something just shy of a 20-point swing.

All of this of course also assumes a uniform national swing. While UNS is usually a fairly reliable predictor of results, it rarely captures the correct seat distributions and, as such, isolated stories and cases of parties doing particularly better in one place versus the next.

For instance, a phenomenon called the ‘first term incumbency bonus’, or ‘sophomore surge’, could produce a situation where Labour underperform national swing in many key marginals. According to this psephological theory, incumbents defending their seat for the first time tend to register a slightly stronger performance than their party does overall at a given election, owing to their ability to build rapport with constituents, take advantage of their significantly elevated personal profile, and the funding and opportunities provided by parliamentary offices.

In 2019, the sophomore effect is estimated to have stopped around 5 extra seats falling from Labour to the Conservatives (according to analysis by John Curtice, Stephen Fisher, and myself). With so many Conservative first-time incumbents scattered across the country after the Red Wall collapse in 2019, the same effect might help some freshly minted Tory MPs stand against the coming red tide.

That said, it is also possible that Labour outperforms uniform swing. Indeed, this happened recently in 2019, when the Conservatives outperformed a uniform projection by 14 seats. The exact same happened in 2010, when Cameron’s party outdid uniform swing again by 14 seats, greatly changing the complexion of the hung parliament to come, according to analysis by Mark Pack.

Whatever the particular situation seat-to-seat, the importance of the scale of Labour’s 2019 cannot be forgotten when we interpret the polls and the likely scenarios ahead of the next General Election – whenever that may be. The shift required to take Labour from their worst result in post-war history to governing with their own majority is no small thing.